Fritz Lang's Architectural Psychology

Space as character

Fritz Lang's masterful manipulation of architectural space transformed cinema by turning buildings and urban environments into psychological extensions of his characters' inner turmoil.

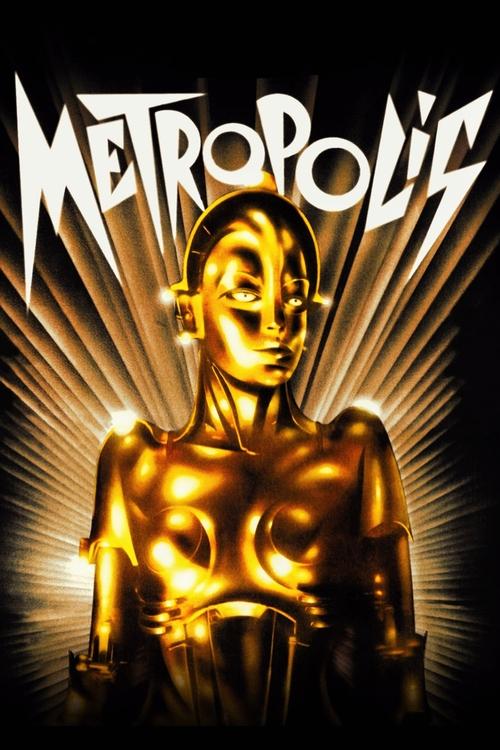

In Weimar-era Germany, Fritz Lang pioneered the use of architecture as a narrative device, drawing heavily from the Expressionist movement's distorted perspectives and imposing structures. His 1927 masterpiece "Metropolis" represents the pinnacle of this approach, with its towering art deco cityscapes serving as physical manifestations of class struggle and social hierarchy. The film's famous Tower of Babel sequence, with its geometric patterns and overwhelming scale, creates a visceral sense of human insignificance against industrial might. Lang worked closely with cinematographer Karl Freund and art directors Otto Hunte and Erich Kettelhut to achieve these effects through a combination of practical sets, forced perspective, and the innovative Schüfftan process of mirror effects.

Lang's 1931 thriller "M" demonstrates his evolution in using architecture to create psychological tension. Moving away from expressionist extremes, he employed a more naturalistic but equally effective approach to Berlin's urban landscape. The film's use of staircases, narrow alleys, and shadowy underpasses creates a labyrinthine nightmare that mirrors the moral maze of its child-killer protagonist. Lang's camera movements through these spaces, particularly in the famous final chase sequence, established techniques that would later influence film noir. The director's careful blocking of scenes within architectural frameworks creates both literal and metaphorical traps, with buildings becoming active participants in the narrative.

Upon emigrating to America, Lang adapted his architectural psychology to Hollywood's film noir style. In "Secret Beyond the Door" (1947), he transformed domestic architecture into a psychological battleground, with each room representing a murder scene and the house itself becoming a manifestation of mental instability. The film's use of interior spaces draws direct connections between architecture and psychoanalysis, reflecting post-war America's fascination with Freudian theory. Lang's camera movement through these spaces creates a sense of claustrophobic tension, with doorways and corridors serving as transitions between conscious and unconscious realms.

Lang's technical innovations in "The Woman in the Window" (1944) demonstrated his ability to use architectural space for narrative revelation. The film's famous mirror sequences and window compositions create multiple layers of reality, with glass and reflective surfaces serving as portals between worlds. His collaboration with cinematographer Milton Krasner established new standards for lighting architectural spaces, particularly in their use of venetian blind shadows and geometric patterns to suggest psychological imprisonment. The film's careful composition of interior spaces creates a visual language of entrapment that would influence generations of filmmakers.

Lang's architectural psychology directly influenced filmmakers from Hitchcock to Kubrick. His technique of using buildings as external manifestations of internal states can be seen in films like "Blade Runner" (1982) and "Inception" (2010). The vertical social hierarchy of "Metropolis" inspired everything from "High-Rise" (2015) to "Snowpiercer" (2013). His innovative use of staircases and elevators as symbols of social mobility and psychological descent appears in contemporary works like "Parasite" (2019). The psychological weight he gave to urban spaces continues to influence directors like Christopher Nolan and David Fincher.

More Ideas

More from Acclaimed Directors

The Coen Brothers: Genre Pastiche & Visual Wit

Postmodern storytellers

Christopher Nolan: Time, Memory & IMAX Spectacle

Puzzle box narratives

Denis Villeneuve: Sci-Fi Atmosphere & Scale

Thoughtful spectacle

Jordan Peele: Horror Through Social Commentary

Genre as activism

Frederick Wiseman: Institutional Observer

Fly-on-the-wall realism

Errol Morris: Truth Detective

Investigation through film

Michael Moore: Provocateur Documentarian

Political activism through cinema