Italian Neorealism: Truth in Cinema

Post-war authenticity

In the rubble of post-WWII Italy, a revolutionary film movement emerged that would forever change how cinema captured human truth and social reality.

Italian Neorealism arose from the ashes of Fascist-controlled cinema, rejecting artificial studio productions in favor of raw authenticity. Filmmakers like Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica took their cameras to the streets, filming non-professional actors amid the actual ruins of war-torn Italy. This radical approach was born partly from necessity—with Cinecittà studios damaged by bombing and economic resources scarce—but it evolved into a powerful artistic philosophy. The movement's commitment to social realism and unvarnished truth-telling created a new film language that influenced generations of directors worldwide.

Neorealist filmmakers developed distinctive technical approaches that became hallmarks of the movement. Working with limited equipment and resources, cinematographers like G.R. Aldo pioneered a documentary-like aesthetic using natural lighting and handheld cameras. Films were often shot without synchronized sound, with dialogue dubbed later—a limitation that paradoxically enhanced the visual storytelling. The use of actual locations rather than sets created a profound sense of place, while long takes and wide shots allowed scenes to unfold with minimal manipulation, establishing a new kind of cinematic truth.

At its core, Neorealism was deeply concerned with examining post-war Italian society's struggles and inequalities. Films focused on ordinary people—workers, peasants, the unemployed—facing daily challenges of survival. Directors like De Sica and Visconti crafted narratives that merged social criticism with profound humanism. The movement rejected melodramatic conventions, instead finding drama in everyday life and dignity in common struggles. This approach revolutionized storytelling, demonstrating how political commentary could be woven naturally into human narratives.

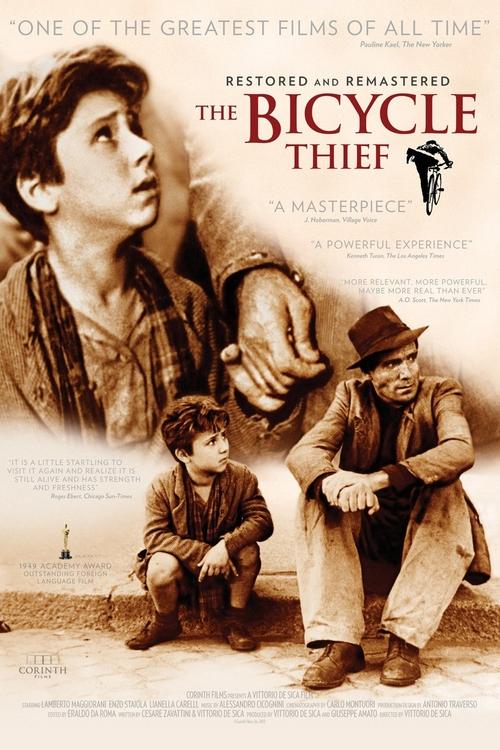

The use of non-professional actors was perhaps Neorealism's most radical innovation. Directors cast ordinary people who naturally embodied their characters' social conditions and experiences. This approach produced performances of startling authenticity, as seen in the work of Lamberto Maggiorani in Bicycle Thieves and Enzo Staiola as his son. The method required directors to develop new techniques for working with untrained performers, often building scenes around their natural behaviors rather than traditional acting methods.

Italian Neorealism's influence extended far beyond Italy's borders, inspiring new waves of cinema worldwide. The movement's techniques and philosophical approach influenced French New Wave directors like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, Indian filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, and Latin American directors developing Third Cinema. The emphasis on social reality and authentic representation continues to influence contemporary filmmakers, from Ken Loach to the Dardenne brothers, who carry forward Neorealism's commitment to addressing social issues through cinema.

More Ideas

The Children Are Watching Us

(1944)

Early De Sica film showing transition to neorealism

Streaming on Criterion Channel

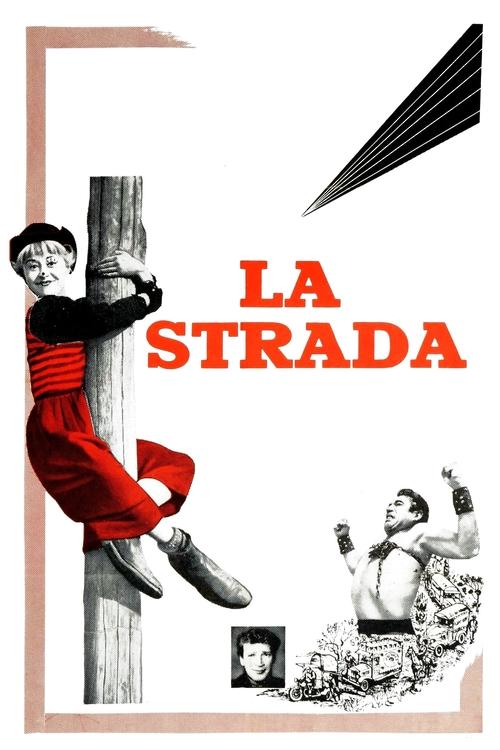

La Strada

(1954)

Fellini's bridge between neorealism and new expressionism

Streaming on HBO Max

The Earth Trembles

(1948)

Visconti's study of Sicilian fishing community

Streaming on Criterion Channel

More from Movements in Film

French New Wave: Breathless Revolution

Godard and Truffaut's innovation

British Kitchen Sink & Social Realism

Working class stories

Japanese New Wave: Oshima & Imamura

Breaking tradition

Czech New Wave: Behind Iron Curtain

Political allegory and freedom

German New Cinema: Herzog & Fassbinder

Post-war artistic renewal

German Expressionism & Silent Era

Visual psychology emerges