1970s: The Auteur Renaissance

Directors take control

The 1970s marked a revolutionary period in American cinema when a generation of young directors seized control of Hollywood, creating personal, uncompromising films that redefined what commercial movies could be. This auteur renaissance emerged from the collapse of the studio system and the cultural upheaval of the era, producing some of the most influential and enduring films in cinema history.

The decade began with the shocking success of "Easy Rider" (1969), which proved that low-budget, director-driven films could achieve massive commercial success. Dennis Hopper's road movie cost just $400,000 but earned over $60 million, demonstrating that audiences hungered for authentic, rebellious voices. The film's success opened doors for a new generation of filmmakers who had studied cinema at places like USC and NYU, bringing both technical knowledge and countercultural sensibilities to Hollywood. Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg would all benefit from this shift, creating the template for the modern blockbuster while maintaining artistic integrity.

Francis Ford Coppola's "The Godfather" (1972) proved that personal vision and commercial success weren't mutually exclusive. Coppola fought studio executives to cast Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, insisting on an authentic Italian-American perspective rather than the typical Hollywood gangster treatment. His collaboration with cinematographer Gordon Willis created the film's signature darkness, using shadows and underexposure to suggest the moral complexity of the Corleone family. The film's massive success—it became the highest-grossing film of its time—gave Coppola the power to make increasingly personal projects like "The Conversation" (1974) and "Apocalypse Now" (1979), establishing the model for director-driven Hollywood filmmaking.

Martin Scorsese emerged as the poet of urban alienation, bringing documentary-style realism to narrative filmmaking. "Mean Streets" (1973) established his signature style—improvised dialogue, handheld cameras, and rock music soundtracks that created an immersive sense of place and character. His collaboration with Robert De Niro in "Taxi Driver" (1976) created one of cinema's most complex antihero studies, with Michael Ballhaus's cinematography capturing the paranoid isolation of urban life. Sidney Lumet's "Serpico" (1973) and "Dog Day Afternoon" (1975) similarly used New York locations to explore corruption and social breakdown, while Hal Ashby's "The Last Detail" (1973) brought the same uncompromising realism to military life.

Steven Spielberg and George Lucas revolutionized commercial filmmaking while maintaining the decade's emphasis on directorial vision. "Jaws" (1975) and "Star Wars" (1977) created the modern blockbuster template—high-concept stories, cutting-edge technical effects, and massive marketing campaigns. Yet both films reflected their directors' personal obsessions: Spielberg's fascination with mechanical creatures and suburban anxiety, Lucas's love of Flash Gordon serials and anthropological storytelling. The success of these films established the economic model that would dominate Hollywood for decades, while proving that personal filmmaking and mass entertainment could coexist. Their influence extends beyond commercial considerations to fundamentally changing how audiences experience cinema.

More Ideas

Five Easy Pieces

(1970)

Jack Nicholson's defining performance in this character study of alienation

Streaming on Criterion Channel

Network

(1976)

Prescient satire of television and corporate media

Streaming on HBO Max

Dog Day Afternoon

(1975)

Based on a true story of a bank robbery gone wrong

Streaming on HBO Max

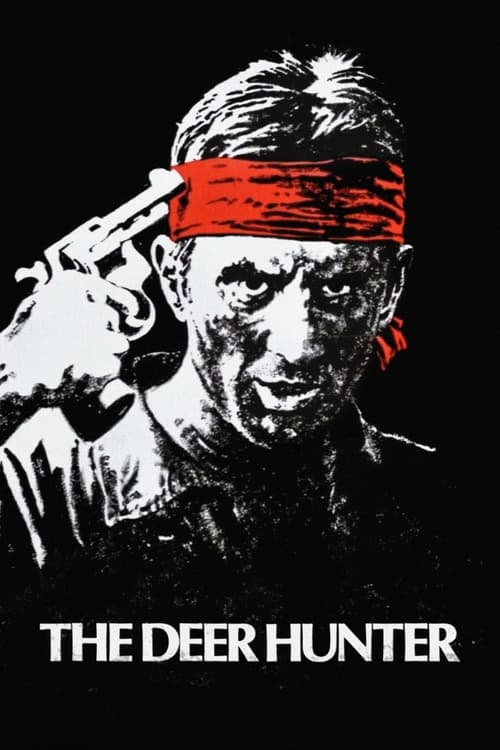

The Deer Hunter

(1978)

Epic examination of the Vietnam War's impact on American life

Streaming on Netflix