Chantal Akerman: Radical Minimalism

Feminist time and space

Chantal Akerman revolutionized feminist cinema through her radical approach to time, space, and the female experience, most notably in her masterpiece "Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles" (1975).

Akerman emerged in the 1970s as part of a wave of feminist filmmakers challenging traditional cinematic language. Her distinctive style developed from both structural film influences and her Jewish-Belgian background, particularly her mother's experiences as a Holocaust survivor. Akerman's approach to duration and the mundane aspects of women's lives created a new feminist aesthetic that forced viewers to confront the reality of domestic labor and female isolation. Her use of static camera positions, long takes, and minimal dialogue established a formal rigor that influenced generations of experimental filmmakers.

Featured Films

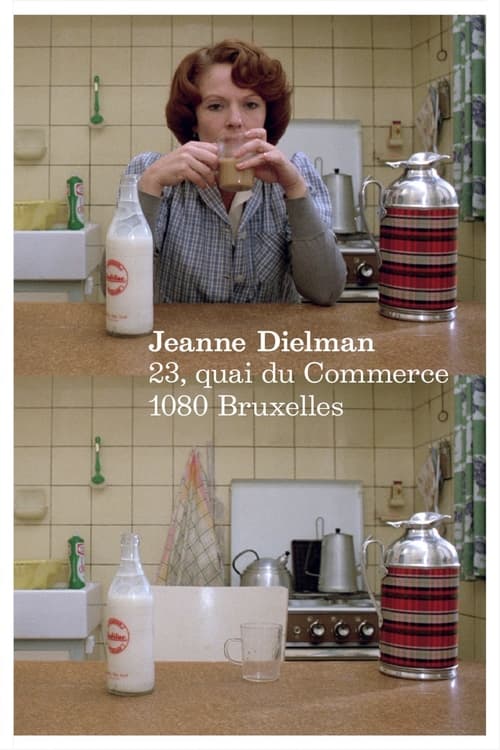

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

(1975)

A masterwork of feminist cinema following three days in a widow's life through rigid domestic routines

Streaming on Criterion Channel

News from Home

(1977)

Akerman reads letters from her mother over long takes of 1970s New York City

Streaming on Criterion Channel

In "Jeanne Dielman," Akerman's most celebrated work, she transforms over three hours of screen time into a radical feminist statement. The film meticulously documents a widow's daily routines - making beds, preparing meals, entertaining male clients - through fixed camera positions and real-time duration. This approach forces viewers to experience the weight of domestic labor typically rendered invisible in cinema. The film's infamous conclusion, where the protagonist commits a shocking act of violence, emerges organically from the accumulated tension of these precisely observed routines.

Akerman's Jewish identity and her family's Holocaust history profoundly influenced her work on displacement and memory. "News from Home" (1977) creates a powerful meditation on distance and belonging by contrasting images of New York City with letters from her mother in Brussels. The film's extended shots of urban spaces, combined with the intimate voiceover, establish a complex dialogue between presence and absence. Similarly, "D'Est" (1993) traces a journey through Eastern Europe after the fall of communism, creating a haunting document of transition and cultural memory through Akerman's characteristic long takes and careful attention to faces and spaces.

Akerman's visual strategy consistently emphasized what she called "images between images." Her static camera positions and extended durational shots create a contemplative space where viewers must actively engage with time and composition. In "Les Rendez-vous d'Anna" (1978), she uses architectural framing and empty spaces to emphasize the protagonist's alienation during a promotional tour. The film's careful composition of hotel rooms, train stations, and transitional spaces reflects Akerman's ongoing interest in how physical environments shape human experience and memory.

Akerman's influence extends far beyond feminist cinema, impacting contemporary art and experimental film. Her installation work, including "NOW" (2015), transferred her cinematic concerns with time and space into gallery contexts. Her approach to duration and domestic space can be seen in the work of contemporary filmmakers like Kelly Reichardt and Joanna Hogg. The recent restoration and wider availability of "Jeanne Dielman" has introduced her work to new generations, confirming her position as a pivotal figure in both feminist and avant-garde cinema.

More Ideas

South

(1999)

Documentary examining American racial history through James Baldwin's perspective

Streaming on Criterion Channel

Tomorrow We Move

(2004)

Comedy about mother-daughter relationships and displacement

Streaming on MUBI

Almayer's Folly

(2011)

Adaptation of Joseph Conrad exploring colonialism and identity

Streaming on Criterion Channel

More from Women Directors

Silent Era Pioneers: Weber & Pickford

Early women behind the camera

Ida Lupino: The Forgotten Auteur

Actor-director breaking barriers

Jane Campion: Feminine Gothic

New Zealand's poetic vision

Kathryn Bigelow: Action Auteur

Redefining genre filmmaking

Contemporary Voices: Gerwig to Zhao

New generation storytellers