Ida Lupino: The Forgotten Auteur

Actor-director breaking barriers

In an era when female directors were virtually nonexistent in Hollywood, Ida Lupino blazed a revolutionary trail as both a celebrated actress and groundbreaking director, tackling controversial subjects that major studios wouldn't touch.

Lupino's transition from actress to director in the late 1940s marked a singular achievement in Hollywood history. After establishing herself as a compelling dramatic actress in films like "High Sierra" (1941) and "The Hard Way" (1943), Lupino became frustrated with the limitations of studio system roles. In 1949, she co-founded The Filmakers, an independent production company, becoming the first woman to produce, direct, and write major American films since Dorothy Arzner. Her directorial debut "Not Wanted" (1949) demonstrated her willingness to tackle taboo subjects, focusing on unwed motherhood with a documentary-like realism that distinguished her work from mainstream Hollywood productions.

Lupino's directorial style emerged from both necessity and artistic vision. Working with limited budgets, she developed a neo-realist approach that emphasized location shooting and naturalistic performances. Her 1950 film "Outrage" was one of the first American films to deal directly with rape and its psychological aftermath. The film showcased Lupino's ability to handle sensitive subject matter with both gravity and empathy, using innovative cinematography and editing techniques to convey trauma without exploitation. Her use of subjective camera angles and expressionistic lighting would influence later filmmakers dealing with psychological subjects.

"The Hitch-Hiker" (1953) represents Lupino's masterpiece of tension and technical precision. As the first film noir directed by a woman, it showcases her mastery of the genre's visual language while subverting its typical gender dynamics. Shot by Nicholas Musuraca, who had photographed many classic noirs, the film demonstrates Lupino's sophisticated understanding of light and shadow. She employed unusual camera angles and claustrophobic framing to heighten tension, particularly in the car scenes where three characters are trapped in close quarters. The film's desert locations are used to create both physical and psychological isolation, with Lupino's direction emphasizing the vastness of the landscape against the intimate human drama.

Lupino's influence extended beyond feature films into television, where she became one of the medium's most prolific directors. Between 1956 and 1968, she directed episodes of over 100 television series, including "The Twilight Zone," "Alfred Hitchcock Presents," and "The Fugitive." Her television work demonstrated remarkable versatility across genres while maintaining her characteristic attention to psychological detail and social issues. These contributions helped establish the visual language of television drama, with her innovative use of close-ups and subjective camera work becoming standard techniques in television direction.

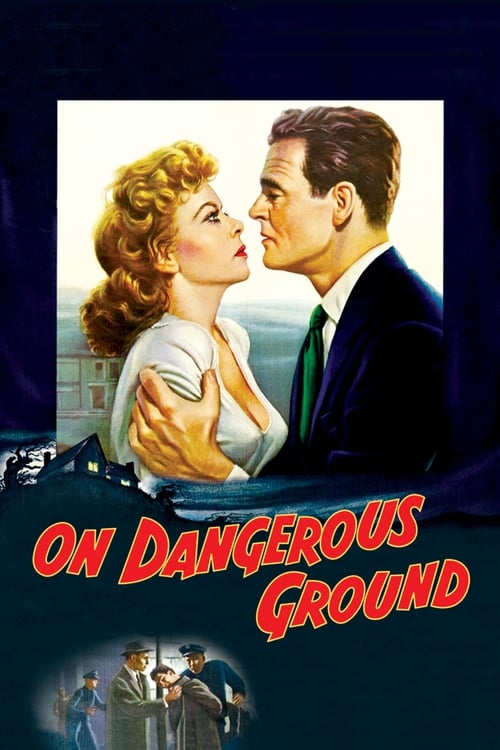

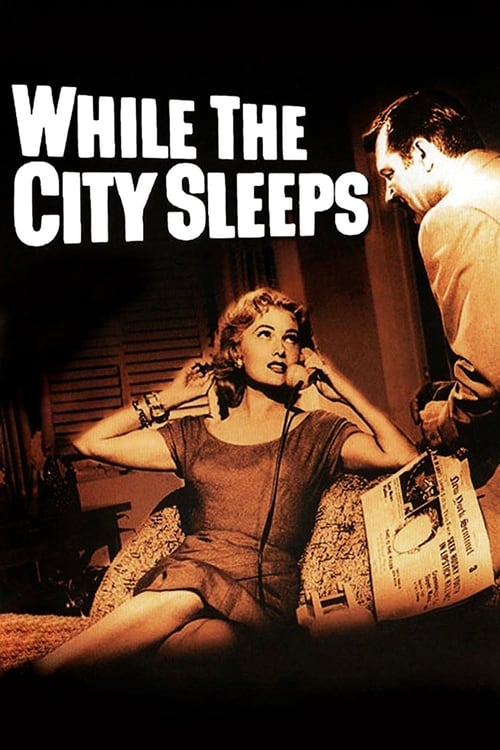

Throughout her directorial career, Lupino continued acting, bringing nuanced performances to films like "On Dangerous Ground" (1951) and "While the City Sleeps" (1956). This dual career provided her with unique insights into performance direction. Her experience in front of the camera informed her directorial approach, particularly in working with actors to achieve naturalistic performances. She developed a reputation for being able to elicit powerful emotional performances while maintaining technical precision, a skill that influenced later actor-directors like Clint Eastwood and Robert Redford.

Lupino's groundbreaking career created a template for independent filmmaking that remains relevant today. Her ability to work outside the studio system while addressing controversial subjects anticipated the American independent film movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Contemporary filmmakers like Kathryn Bigelow and Jane Campion have acknowledged Lupino's influence, particularly in handling genre material with psychological depth. Her work demonstrated that films addressing serious social issues could be both commercially viable and artistically significant, helping pave the way for issue-driven cinema of subsequent decades.

More Ideas

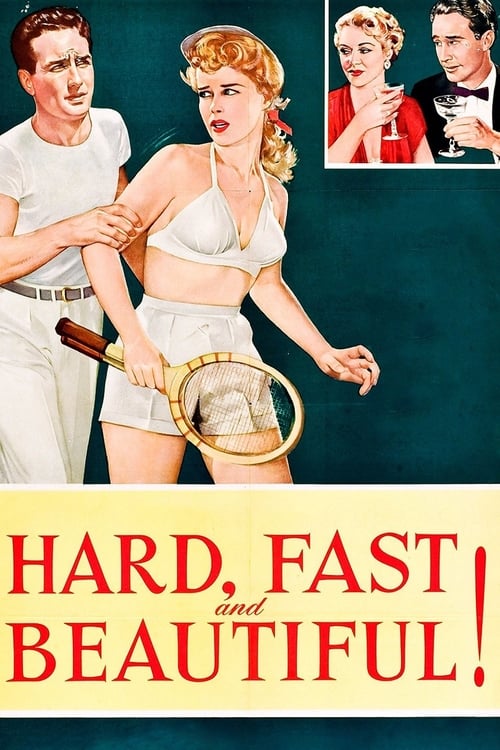

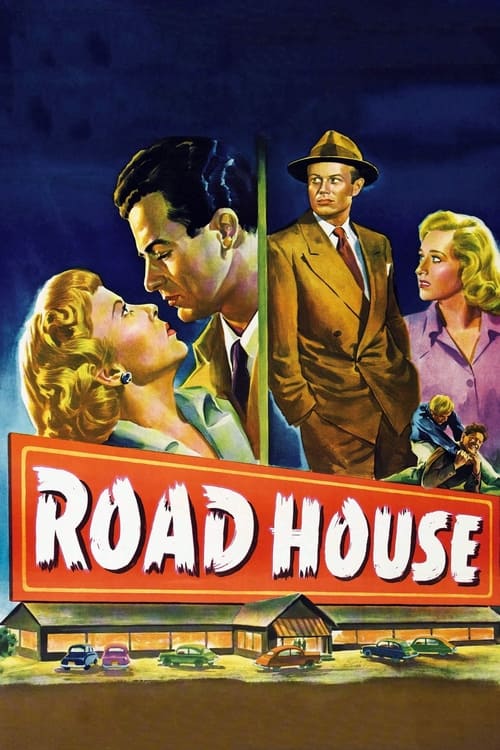

Road House

(1948)

Film noir showcasing Lupino's acting range

Streaming on TCM

Never Fear

(1949)

Lupino's semi-autobiographical directorial work about polio

Streaming on Criterion Channel

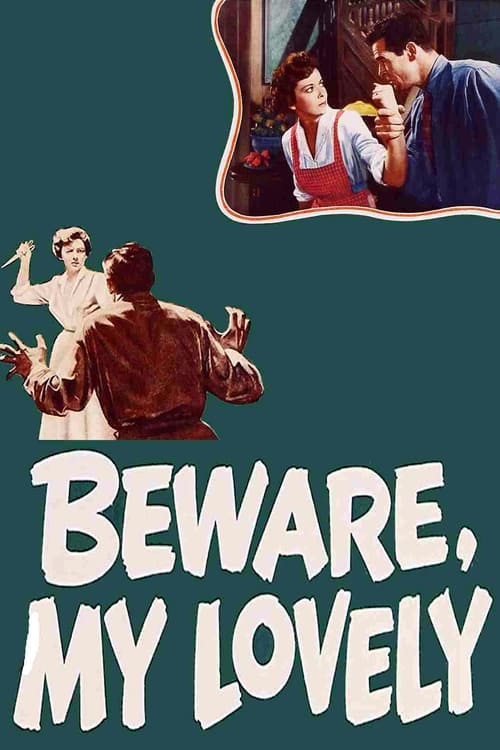

Beware, My Lovely

(1952)

Psychological thriller starring Lupino

Streaming on Prime Video

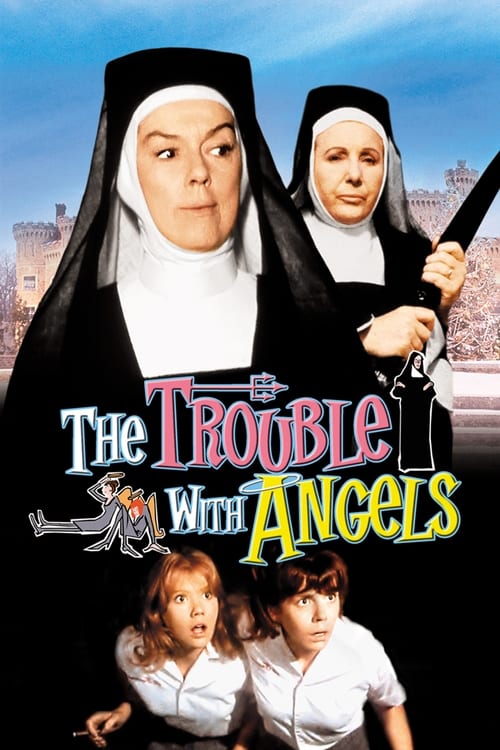

The Trouble with Angels

(1966)

Comedy demonstrating Lupino's versatility as director

Streaming on TCM