International Cinema Breaks Through

World cinema reaches America

The 1950s and 60s marked a revolutionary period when international cinema finally penetrated American consciousness, forever transforming the landscape of film culture in the United States.

The post-World War II era created unique conditions for foreign films to reach American audiences. As soldiers returned from Europe and Japan with broadened worldviews, art house theaters began sprouting in major cities, catering to more sophisticated tastes. Akira Kurosawa's "Rashomon" (1950) became a watershed moment, winning the Golden Lion at Venice and the Academy Honorary Award, demonstrating that subtitled films could find success with American audiences. The film's innovative narrative structure, telling the same story from multiple perspectives, challenged Hollywood's conventional storytelling methods and introduced American viewers to Japanese cinema's artistic possibilities.

The French New Wave crashed onto American shores in the late 1950s, revolutionizing cinema language and inspiring a generation of American filmmakers. François Truffaut's "The 400 Blows" (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's "Breathless" (1960) introduced American audiences to a new cinematic grammar: jump cuts, handheld cameras, location shooting, and natural lighting. These techniques, born from necessity and artistic innovation, would later influence American New Hollywood directors like Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. The movement's emphasis on personal expression and formal experimentation challenged Hollywood's polished studio system.

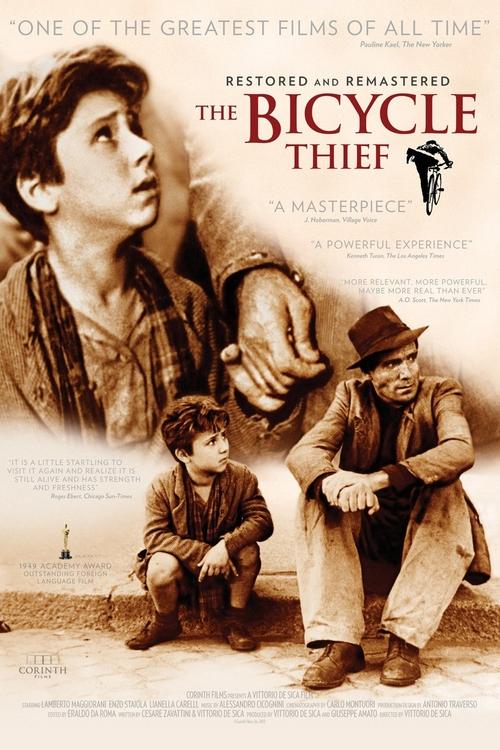

Italian Neorealism had already begun making inroads in the late 1940s, but it was Federico Fellini's "La Dolce Vita" (1960) that truly captured American attention. The film's exploration of celebrity culture and moral decay in modern society resonated with American audiences, while its sophisticated visual style and complex narrative structure elevated international cinema's reputation. Vittorio De Sica's earlier works like "Bicycle Thieves" (1948) had demonstrated the power of social realism, but Fellini's more flamboyant style showed that European cinema could be both artistically ambitious and commercially viable.

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman became particularly influential in American intellectual circles during this period. His psychological dramas like "The Seventh Seal" (1957) and "Persona" (1966) demonstrated that cinema could tackle profound philosophical and existential themes with the same depth as literature. Bergman's work, photographed by the legendary Sven Nykvist, established a new standard for cinematographic excellence and psychological complexity in filmmaking, influencing countless American directors including Woody Allen and Robert Altman.

Japanese cinema continued its impact through the 1960s, with directors like Yasujirō Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi gaining recognition alongside Kurosawa. Ozu's "Tokyo Story" (1953) introduced Americans to a completely different rhythm of filmmaking, with its contemplative pacing and low-angle static shots becoming influential stylistic choices. The film's universal themes of family dynamics and generational conflict resonated deeply with American audiences, proving that cultural barriers could be transcended through masterful storytelling.

The success of international cinema in America led to significant changes in distribution and exhibition. Janus Films, founded in 1956, became instrumental in importing and distributing foreign films, while the Criterion Collection, launched in 1984, would later ensure their preservation and availability. Art house theaters proliferated in urban centers, creating dedicated spaces for international cinema. This infrastructure development was crucial in sustaining the foreign film market in America and nurturing a more cinematically literate audience.

By the late 1960s, international cinema had profoundly influenced American filmmaking. The emergence of New Hollywood directors like Arthur Penn and Mike Nichols showed clear traces of European influence in both style and content. "Bonnie and Clyde" (1967) drew heavily from French New Wave techniques, while "The Graduate" (1967) exhibited European-style social criticism and formal innovation. This cross-pollination of cinematic styles and ideas helped create a more sophisticated American cinema.

More Ideas

High and Low

(1963)

Kurosawa's noir-influenced crime drama

Streaming on Criterion Channel

Jules and Jim

(1962)

Truffaut's innovative love triangle story

Streaming on Criterion Channel

8½

(1963)

Fellini's surrealist masterpiece about creative crisis

Streaming on HBO Max

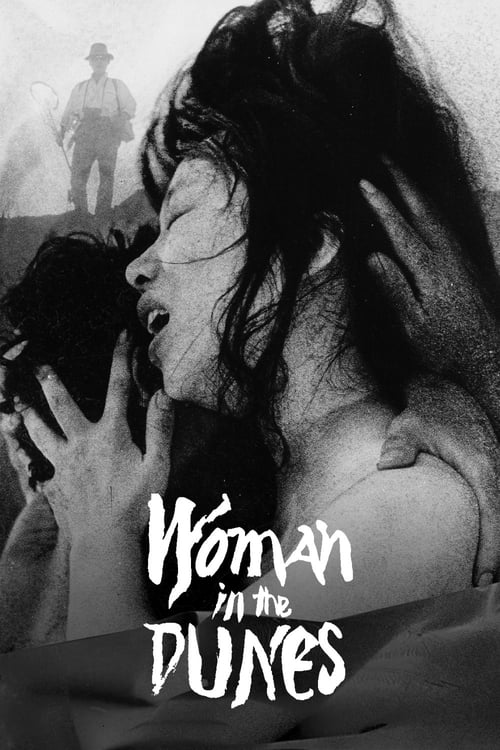

Woman in the Dunes

(1964)

Teshigahara's avant-garde Japanese classic

Streaming on Criterion Channel

More from Hollywood Transformed

WWII & Cinema's War Effort

Movies as propaganda and art

Independent Film Renaissance

Breaking free from studios

Franchise Filmmaking Dominance

Sequels and shared universes

Streaming Changes Everything

Netflix revolutionizes distribution

Marvel & the Cinematic Universe

Superhero storytelling dominates

A24 & Independent Prestige

Art house meets commercial success

International Streaming Wars

Global content competition

Post-Pandemic Cinema

How COVID changed moviegoing

From Weimar to Hollywood: The Émigré Influence

European artistry in America