WWII & Cinema's War Effort

Movies as propaganda and art

World War II fundamentally transformed cinema, as governments harnessed the power of film both as a propaganda tool and as a means of documenting humanity's greatest conflict.

The outbreak of WWII saw an unprecedented mobilization of the film industry, particularly in the United States following Pearl Harbor. Hollywood studios worked directly with the Office of War Information (OWI) to produce films that would boost morale and support the war effort. Frank Capra's "Why We Fight" series (1942-1945) exemplified this partnership, combining captured enemy footage with powerful narration to explain the war's causes and justify American involvement. The series demonstrated how documentary techniques could be merged with dramatic storytelling to create compelling propaganda that still maintained artistic merit.

British filmmakers faced unique challenges producing films during active bombing campaigns, yet created some of the era's most powerful works. Powell and Pressburger's "49th Parallel" (1941) was explicitly commissioned as propaganda but transcended its origins through innovative cinematography and complex characterization. Their follow-up "The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp" (1943) proved more controversial, offering a nuanced view of German-British relations that Churchill initially attempted to suppress. Humphrey Jennings' documentary "Listen to Britain" (1942) captured everyday wartime life with poetic realism that influenced documentary filmmaking for decades.

The Nazi regime's approach to cinema was epitomized by Leni Riefenstahl's technical mastery put to disturbing use. While "Triumph of the Will" (1935) predated the war, its techniques influenced wartime propaganda globally. The anti-Semitic "Jud Süß" (1940) demonstrated how narrative fiction could be weaponized for hatred. In contrast, Hollywood's anti-Nazi films like "Casablanca" (1942) and "To Be or Not to Be" (1942) used sophisticated satire and romance to counter fascist ideology while creating enduring art. These films showcased how entertainment could carry serious political messages without sacrificing artistic quality.

Japanese cinema during WWII reflected the militaristic government's tight control, with directors like Akira Kurosawa forced to make nationalist films. His "The Most Beautiful" (1944) about female factory workers superficially supported the war effort while subtly highlighting the human cost. Post-war, Japanese directors like Kon Ichikawa would revisit the period with unflinching works like "The Burmese Harp" (1956), examining war's moral complexity and devastating impact on soldiers' humanity.

The war years saw significant technical innovations in combat photography. John Ford's "The Battle of Midway" (1942) brought color footage of actual combat to audiences, while Soviet cinematographers like Roman Karmen developed new techniques for filming under battlefield conditions. These advances influenced post-war cinema, particularly the Italian Neorealist movement, which adopted documentary-style techniques to depict war's aftermath in films like Roberto Rossellini's "Rome, Open City" (1945).

Hollywood's war films evolved from early propaganda pieces to more complex narratives as the conflict progressed. William Wyler's "The Best Years of Our Lives" (1946) examined veterans' readjustment to civilian life with unprecedented realism, while Lewis Milestone's "A Walk in the Sun" (1945) portrayed combat with documentary-like authenticity. These films established templates for war cinema that would influence generations of filmmakers, balancing patriotic sentiment with increasingly realistic depictions of combat and its psychological toll.

The war's impact extended to animation, with Walt Disney studios producing training films and propaganda pieces like "Victory Through Air Power" (1943). Warner Bros. cartoons featured characters like Bugs Bunny battling caricatured Japanese and German enemies. These works demonstrated animation's potential for both instruction and propaganda, though some now appear problematically racist. Their technical innovations, however, advanced the medium significantly.

More Ideas

In Which We Serve

(1942)

Noël Coward's tribute to Royal Navy service

Streaming on BritBox

Memphis Belle

(1944)

William Wyler's documentary about B-17 bomber crew

Streaming on National Archives

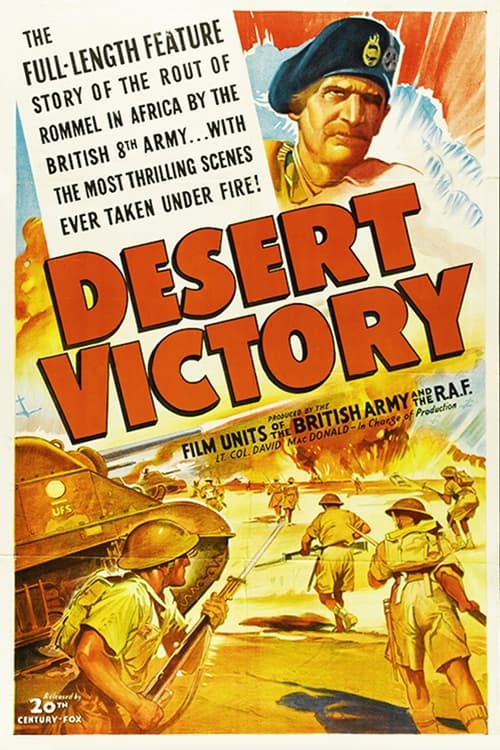

Desert Victory

(1943)

British documentary about North African campaign

Streaming on Imperial War Museum

Tomorrow We Live

(1943)

French resistance drama made during occupation

Streaming on Film Archives

More from Hollywood Transformed

Independent Film Renaissance

Breaking free from studios

International Cinema Breaks Through

World cinema reaches America

Franchise Filmmaking Dominance

Sequels and shared universes

Streaming Changes Everything

Netflix revolutionizes distribution

Marvel & the Cinematic Universe

Superhero storytelling dominates

A24 & Independent Prestige

Art house meets commercial success

International Streaming Wars

Global content competition

Post-Pandemic Cinema

How COVID changed moviegoing

From Weimar to Hollywood: The Émigré Influence

European artistry in America