From Weimar to Hollywood: The Émigré Influence

European artistry in America

The exodus of European filmmaking talent to Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s fundamentally transformed American cinema, bringing sophisticated visual techniques and psychological complexity from German Expressionism to mainstream American films.

The Weimar era (1919-1933) in German cinema produced revolutionary artistic innovations that would later reshape Hollywood storytelling. Directors like F.W. Murnau pioneered expressive camera movements and sophisticated lighting techniques that broke from static theatrical staging. His 1924 film "The Last Laugh" demonstrated how pure visual storytelling could convey complex narratives with minimal intertitles. This technical virtuosity, combined with themes of psychological turmoil and social upheaval, defined the German Expressionist movement. The stark shadows, oblique angles, and distorted perspectives became visual signatures that would later influence film noir and horror genres in Hollywood.

As the Nazi regime consolidated power in the 1930s, an unprecedented migration of film talent fled to Hollywood. Directors like Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, and Otto Preminger brought their distinctive visual style and sophisticated themes to American studios. This influx profoundly influenced Hollywood's aesthetic vocabulary, particularly in the emerging film noir genre. Lang's first American film, "Fury" (1936), merged German Expressionist techniques with American social commentary, while Wilder's "Double Indemnity" (1944) established noir conventions that would define the genre for decades.

The émigré cinematographers had perhaps the most immediate impact on Hollywood's visual language. Karl Freund, who had photographed "Metropolis," brought his mastery of chiaroscuro lighting and fluid camera movement to Universal's horror films. His work on "Dracula" (1931) established the gothic visual template for horror cinema. Similarly, John Alton, born in Hungary and trained in Germany, revolutionized low-key lighting techniques in films like "T-Men" (1947) and "The Big Combo" (1955), creating the signature look of film noir with minimal lighting setups and maximum psychological impact.

The European émigrés brought sophisticated psychological themes to Hollywood narratives. Max Ophüls, who fled Germany in 1933, created elaborate tracking shots that expressed characters' emotional states through camera movement. His "Letter from an Unknown Woman" (1948) demonstrated how technical virtuosity could serve character psychology. Robert Siodmak's "The Spiral Staircase" (1946) incorporated expressionist techniques to visualize psychological terror, while Curtis Bernhardt's "Possessed" (1947) used subjective camera work to portray mental illness with unprecedented complexity.

The émigré influence extended beyond noir into multiple genres. Douglas Sirk (born Detlef Sierck) transformed the American melodrama with his sophisticated visual style and subtle social criticism. His use of color, reflection, and frame composition in films like "All That Heaven Allows" (1955) added layers of meaning to seemingly conventional narratives. Meanwhile, Edgar G. Ulmer brought expressionist techniques to B-movies, creating sophisticated films on minimal budgets, most notably in "Detour" (1945), which achieved remarkable psychological depth despite its limited resources.

The émigré influence continues to resonate in contemporary cinema. Their technical innovations became standard tools in the filmmaker's arsenal, while their sophisticated approach to narrative and psychology helped mature American cinema. Directors like Christopher Nolan have acknowledged their debt to this legacy, with "Inception" (2010) showing clear influences from Lang's architectural sensibility and expressionist distortion of reality. The noir style they helped establish has influenced generations of filmmakers, from Roman Polanski's "Chinatown" (1974) to Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" (1982).

More Ideas

M

(1931)

Lang's German masterpiece before emigration

Streaming on Criterion Channel

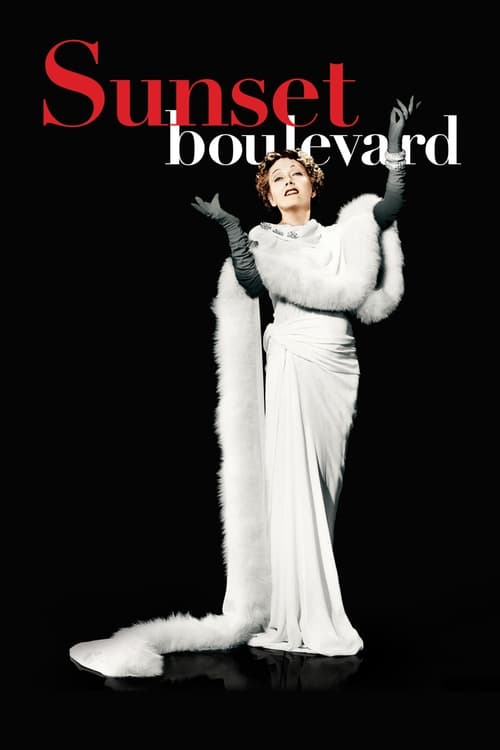

Sunset Boulevard

(1950)

Wilder's Hollywood noir with expressionist touches

Streaming on Paramount+

The Stranger

(1946)

Welles noir thriller with Expressionist influence

Streaming on Public Domain

Ministry of Fear

(1944)

Lang's wartime thriller with psychological depth

Streaming on Criterion Channel

More from Hollywood Transformed

WWII & Cinema's War Effort

Movies as propaganda and art

Independent Film Renaissance

Breaking free from studios

International Cinema Breaks Through

World cinema reaches America

Franchise Filmmaking Dominance

Sequels and shared universes

Streaming Changes Everything

Netflix revolutionizes distribution

Marvel & the Cinematic Universe

Superhero storytelling dominates

A24 & Independent Prestige

Art house meets commercial success

International Streaming Wars

Global content competition

Post-Pandemic Cinema

How COVID changed moviegoing