The femme fatale archetype in film noir represents cinema's most seductive and dangerous incarnation of female power, emerging from the anxieties of post-war America and forever changing how sexuality and gender dynamics were portrayed on screen.

The classic film noir femme fatale emerged in the 1940s as a direct response to shifting gender roles during and after World War II. With millions of women entering the workforce and gaining unprecedented independence, Hollywood reflected growing male anxiety through characters who weaponized their sexuality and intelligence. Double Indemnity (1944) established the archetypal femme fatale through Barbara Stanwyck's masterful portrayal of Phyllis Dietrichson, a calculating wife who manipulates an insurance salesman into murdering her husband. Director Billy Wilder and cinematographer John F. Seitz used shadowy lighting and Dutch angles to emphasize her predatory nature, while the script by Raymond Chandler and Wilder crafted dialogue dripping with innuendo and menace.

The femme fatale represents a complex intersection of male desire and fear, particularly in post-war America's struggle with changing gender dynamics. In Out of the Past (1947), Jane Greer's Kathie Moffat embodies this duality as a woman whose beauty masks lethal intentions. Director Jacques Tourneur crafted scenes where shadow and light play across Greer's face, suggesting the duplicitous nature beneath her angelic appearance. The film's complicated narrative structure, told largely through flashbacks, mirrors the psychological complexity of the femme fatale herself. This approach influenced later neo-noir films like Body Heat (1981), where Kathleen Turner's Matty Walker consciously plays with the archetype while updating it for a more sexually liberated era.

The visual language of the femme fatale became codified through specific cinematographic techniques that emphasized both allure and danger. In The Killers (1946), Ava Gardner's Kitty Collins is introduced through a series of increasingly intimate close-ups, each revealing another layer of her dangerous beauty. Cinematographer Elwood Bredell utilized high-contrast lighting to create stark shadows across her face, suggesting hidden depths and ulterior motives. This visual approach was further refined in The Lady from Shanghai (1947), where Rita Hayworth's character is frequently shot through distorting mirrors and reflective surfaces, fragmenting her image to represent her fractured morality.

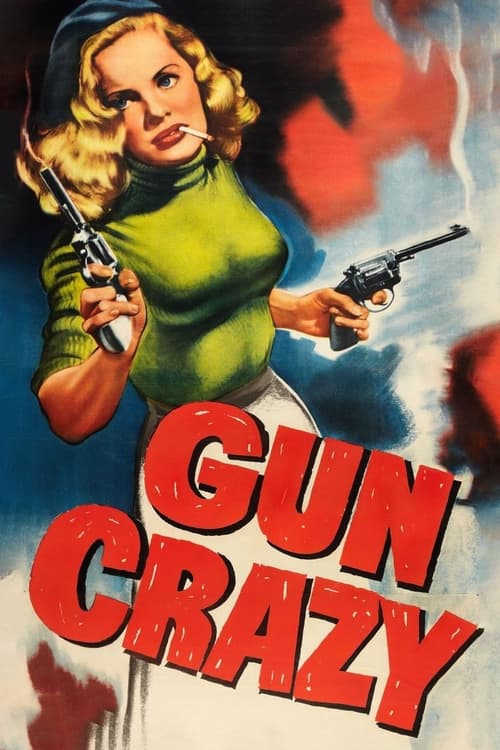

The femme fatale's power often stems from her ability to manipulate masculine systems of control through sexuality and intelligence. In The Maltese Falcon (1941), Mary Astor's Brigid O'Shaughnessy uses performed vulnerability to mask her ruthless nature, playing on societal expectations of feminine weakness. The film's director, John Huston, subverts these expectations by gradually revealing her true nature through subtle performance cues and strategic camera placement. This theme reached its apex in Gun Crazy (1950), where Peggy Cummins' Annie Laurie Starr actively participates in violence rather than merely orchestrating it, representing a more direct challenge to gender norms.

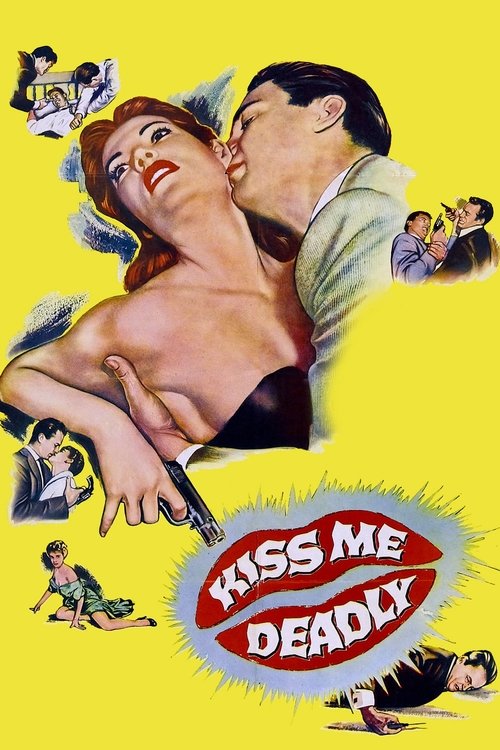

The 1950s saw the femme fatale evolve beyond simple villainy into more psychologically complex territory. In Pickup on South Street (1953), Jean Peters' character subverts expectations by transitioning from apparent femme fatale to sympathetic protagonist, reflecting changing attitudes toward female agency. This evolution continued in Kiss Me Deadly (1955), where Velda and Christina represent different aspects of the archetype, combining sexuality with atomic-age apocalyptic themes. Director Robert Aldrich used their characters to comment on Cold War paranoia while maintaining noir's trademark visual style.

More Ideas

Scarlet Street

(1945)

Joan Bennett plays a ruthless woman who manipulates an artist into crime

Streaming on Criterion Channel

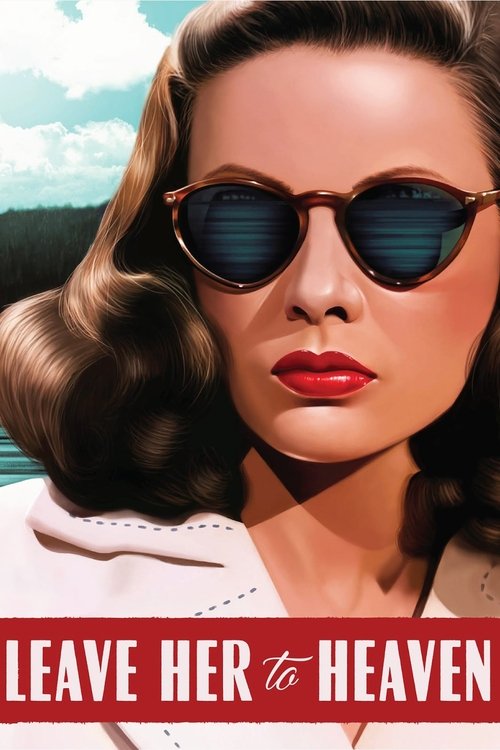

Leave Her to Heaven

(1945)

Gene Tierney stars as a possessive woman whose love turns murderous

Streaming on Prime Video

Basic Instinct

(1992)

Sharon Stone updates the femme fatale for the modern thriller era

Streaming on Netflix

Mulholland Drive

(2001)

David Lynch deconstructs the femme fatale archetype in this neo-noir masterpiece

Streaming on Criterion Channel