Film noir revolutionized cinema by abandoning clear-cut morality in favor of complex characters who inhabited the shadowy space between good and evil.

The post-World War II era ushered in a new cynicism that challenged Hollywood's traditional moral certainties. Directors like Otto Preminger and Billy Wilder crafted protagonists who defied simple categorization, reflecting a society grappling with moral relativism. In "Double Indemnity" (1944), insurance salesman Walter Neff transforms from an ordinary businessman into a calculating murderer, while femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson reveals layers of vulnerability beneath her manipulative exterior. Cinematographer John F. Seitz used harsh lighting and deep shadows to externalize this moral ambiguity, creating visual tension that emphasized characters' internal struggles.

Film noir pioneered the anti-hero archetype, presenting protagonists whose moral compass often pointed in unexpected directions. In "Out of the Past" (1947), Robert Mitchum's Jeff Bailey attempts to escape his criminal history but finds redemption elusive. Director Jacques Tourneur and cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca created a visual language where shadows literally consume characters, suggesting moral darkness seeping into their souls. This theme reached its apex in "Touch of Evil" (1958), where Orson Welles plays a corrupt police captain whose previous good deeds complicate audience sympathies, while Charlton Heston's nominally heroic Mexican prosecutor employs questionable methods.

The femme fatale character particularly embodied noir's moral ambiguity. These women defied traditional victim/villain categorizations, often driven to manipulation and murder by societal constraints. In "The Maltese Falcon" (1941), Mary Astor's Brigid O'Shaughnessy shifts between vulnerable damsel and cold-blooded killer, while Barbara Stanwyck's Phyllis in "Double Indemnity" masks deep emotional wounds behind calculated seduction. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson pioneered techniques like the "Venetian blind" lighting effect, creating literal bars across characters' faces to suggest moral imprisonment.

The 1950s saw noir's moral ambiguity deepen further with films exploring systemic corruption. "The Big Heat" (1953) presents a supposedly righteous police force as deeply compromised, while Glenn Ford's honest cop employs increasingly violent methods. Fritz Lang's direction deliberately blurs the line between law enforcement and criminality, while cinematographer Charles Lang Jr. used high-contrast lighting to suggest moral absolutes dissolving into grey areas. This theme reached its apex in "Sweet Smell of Success" (1957), where Burt Lancaster's powerful columnist and Tony Curtis's press agent represent different shades of moral bankruptcy.

Neo-noir films of the 1970s expanded on classic noir's moral ambiguity. Roman Polanski's "Chinatown" (1974) presents a protagonist whose determination to do right leads to catastrophic consequences, while John Huston's Noah Cross embodies evil masquerading as respectability. Cinematographer John A. Alonzo created a sun-bleached noir look that suggested moral rot in broad daylight. Similarly, "Night Moves" (1975) features Gene Hackman as a private detective whose quest for truth only reveals deeper layers of deception and personal failure.

Contemporary filmmakers continue to draw on noir's tradition of moral ambiguity. Christopher Nolan's "Memento" (2000) uses its protagonist's memory condition to question the nature of justice and revenge, while David Fincher's "Gone Girl" (2014) presents a marriage where both partners inhabit morally grey areas. The influence extends to television, with series like "True Detective" and "Better Call Saul" exploring how good intentions can lead to moral compromise. Modern cinematographers like Roger Deakins and Jeff Cronenweth have developed new visual techniques to portray this ethical uncertainty while paying homage to noir's classical period.

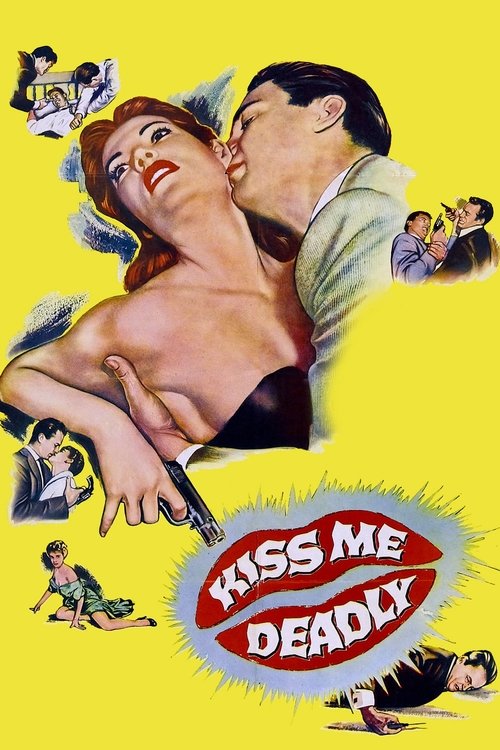

The exploration of moral ambiguity in film noir reflected broader philosophical questions about the nature of good and evil. Films like "Pickup on South Street" (1953) complicated Cold War politics by presenting a petty criminal as an unlikely patriot, while "Kiss Me Deadly" (1955) suggested that those pursuing justice could be as destructive as those they hunted. This sophisticated approach to morality influenced global cinema, from the French New Wave to Japanese noir like "Stray Dog" (1949), where Akira Kurosawa explored how thin the line between detective and criminal could become.

More Ideas

The Killing

(1956)

A complex heist reveals honor among thieves

Streaming on Criterion Channel

In a Lonely Place

(1950)

A volatile screenwriter may or may not be a murderer

Streaming on Prime Video

Kiss Me Deadly

(1955)

A brutal private eye searches for a mysterious package

Streaming on TCM

The Big Sleep

(1946)

A private eye encounters layers of corruption and murder

Streaming on HBO Max