Film noir transformed city streets into shadowy labyrinths of moral corruption, reflecting post-war American anxieties about urban life and societal decay.

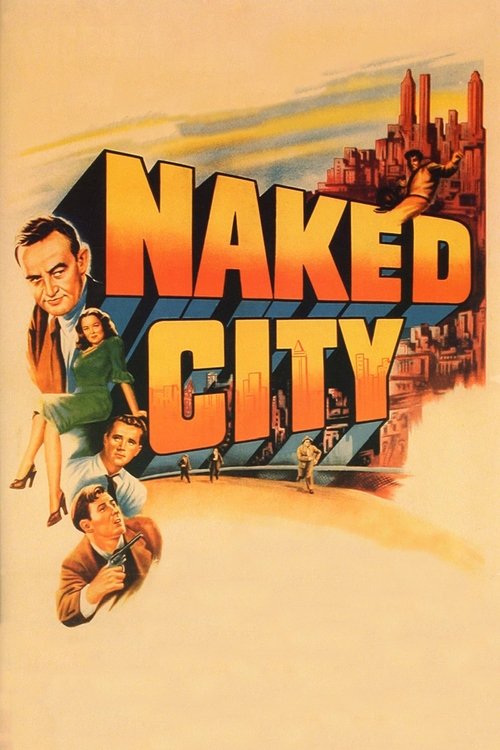

The emergence of film noir in the 1940s coincided with America's rapid urbanization and post-war disillusionment. Directors like Jules Dassin and Otto Preminger utilized stark shadows, canted angles, and rain-slicked streets to create a visual language of urban paranoia. In "The Naked City" (1948), Dassin pioneered on-location shooting in New York, treating the city itself as a character that looms over its inhabitants. The film's documentary-style approach to urban crime established a template for depicting city life as inherently threatening, while cinematographer William Daniels captured the claustrophobic nature of cramped apartments and narrow alleyways that would become noir staples.

Featured Films

The Naked City

(1948)

Revolutionary noir filmed entirely on New York streets, following a police investigation through the city's underbelly

Streaming on Criterion Channel

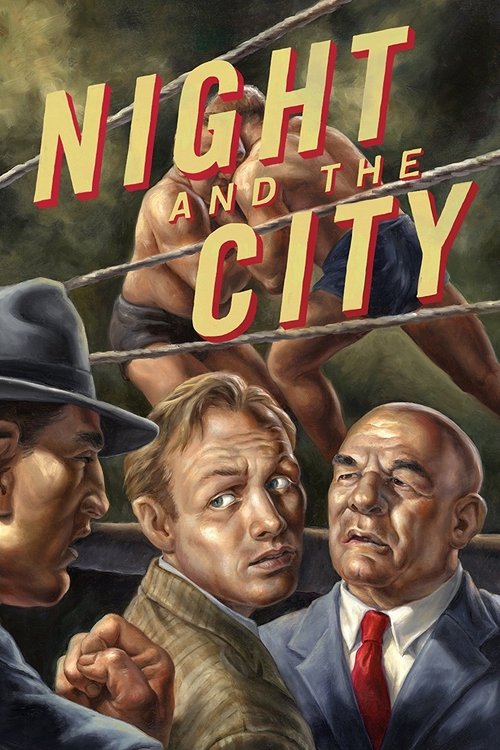

Night and the City

(1950)

Richard Widmark as a small-time hustler in a nightmarish London, directed by Jules Dassin

Streaming on Amazon Prime

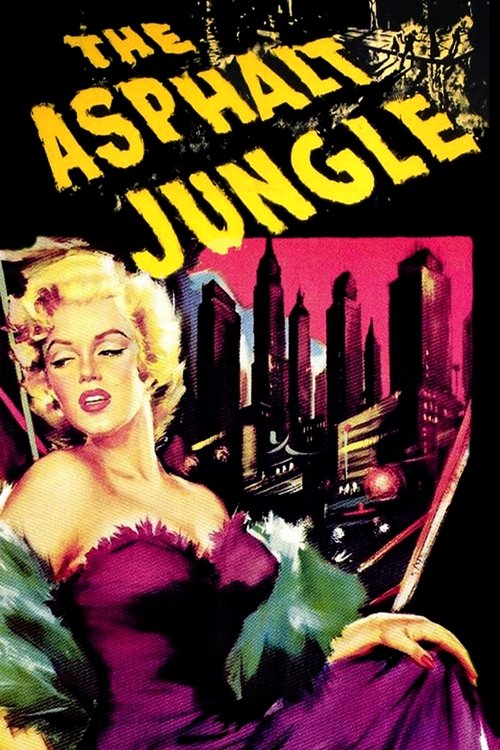

Film noir frequently employed vertical architecture as a metaphor for social and moral hierarchy. In "The Asphalt Jungle" (1950), John Huston explores how the city's physical structure mirrors its social stratification, from basement criminal hideouts to penthouse offices. Cinematographer Harold Rosson created compositions that emphasized towering buildings and deep urban canyons, suggesting characters trapped in an architectural maze. This vertical motif reached its apex in Robert Siodmak's "Criss Cross" (1949), where the Bradbury Building's iconic stairways and elevators become central to the film's exploration of social mobility and moral descent.

The nocturnal city emerged as noir's defining canvas, with cinematographers like John Alton pioneering techniques to capture urban darkness. In "The Big Heat" (1953), Fritz Lang and cinematographer Charles Lang Jr. created a nightmarish vision of urban corruption, where streetlights cast menacing shadows and neon signs illuminate moral compromise. The film's violence erupts in diners, cars, and apartments, suggesting no urban space is safe from corruption. This technique influenced Nicholas Musuraca's work in "Out of the Past" (1947), where the city becomes an expressionist nightmare of black shadows and piercing lights.

Urban alienation found its perfect expression in the anonymous hotel room, a recurring noir location that symbolized rootlessness and moral transience. In "The Killers" (1946), Robert Siodmak used these temporary spaces to explore how urban life dissolves traditional bonds and values. Cinematographer Elwood Bredell created compositions emphasizing isolation, with characters framed alone in stark rooms or separated by architectural elements. This theme reached its pinnacle in Jacques Tourneur's "Out of the Past" (1947), where hotel rooms become stages for betrayal and moral compromise.

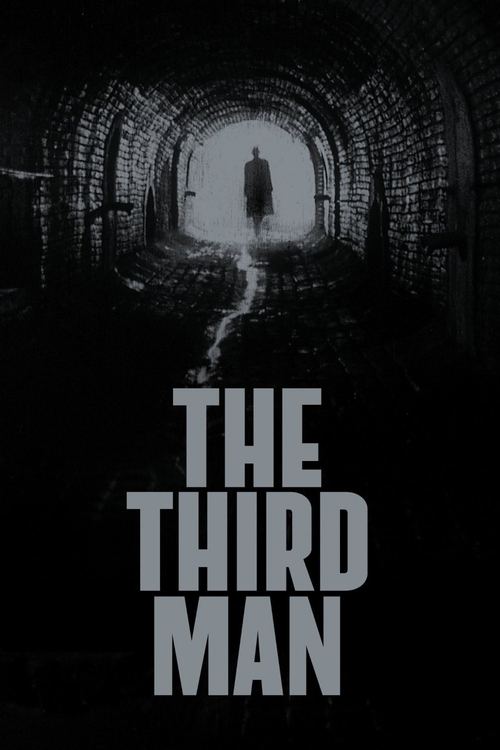

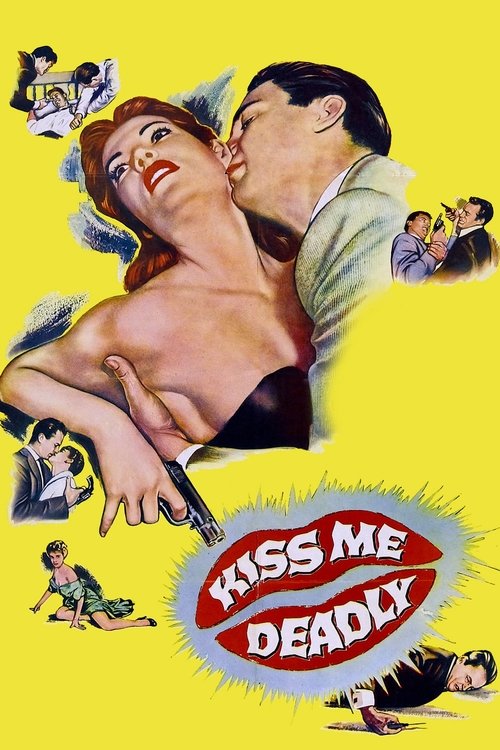

The noir city's public spaces became theaters of paranoia and surveillance. Carol Reed's "The Third Man" (1949) transformed Vienna's sewers and ferris wheel into symbols of post-war moral chaos. Cinematographer Robert Krasker won an Oscar for his tilted compositions and expressionist lighting, creating a city where every shadow could hide a betrayer. This influence is evident in "Kiss Me Deadly" (1955), where Robert Aldrich and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo depicted Los Angeles as a nuclear-age nightmare of suspicious glances and hidden threats.

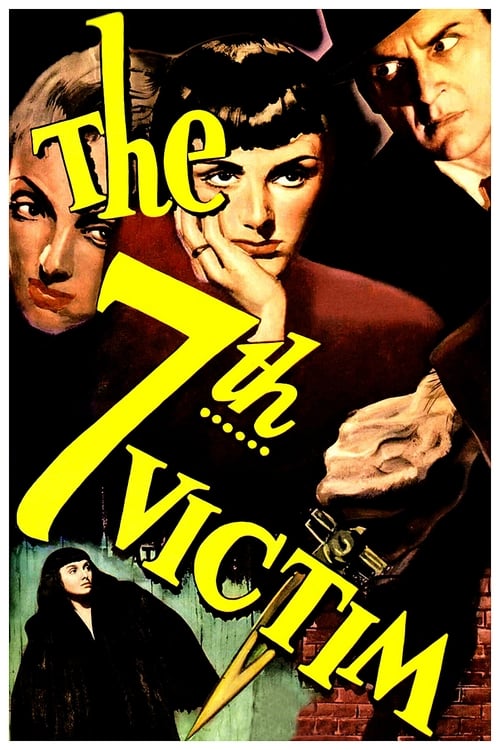

Female characters in noir often embodied urban moral ambiguity, particularly in their relationship to public spaces. In "Pickup on South Street" (1953), Samuel Fuller explored how women navigate the dangerous city, with cinematographer Joe MacDonald creating tense sequences in subway cars and crowded streets. This theme reached its apex in "The Seventh Victim" (1943), where Mark Robson and Nicholas Musuraca created a Greenwich Village where female independence leads to supernatural danger.